We have all read fly patterns that refer to quills, barbs, barbules, fibers, shafts, stems, vanes and so forth, but when we read these terms do we know what they have reference to? This article sets all these terms and many more straight.

We have all read fly patterns that refer to quills, barbs, barbules, fibers, shafts, stems, vanes and so forth, but when we read these terms do we know what they have reference to? This article sets all these terms and many more straight.

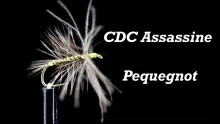

A part of learning to do flies like this one is learning to know the main material: feathers.

We need to have standards

An important aspect of fly tying is sharing information. In turn it behooves us as fly tiers to speak the same language. We have all read fly patterns that refer to quills, barbs, barbules, fibers, shafts, stems, vanes and so forth, but when we read these terms do we know what they have reference to? We may, but what about the author; did he truly describe by name what he intended? How often have we read quill when in fact what was referred to was actually a barb or perhaps shaft? How often have we read fibers when the author meant barbs or perhaps barbules? How often have we read barbs, barbules, fibers or even barbels (which are tactile processes on the lips of a fish rather than components of a feather) when referring to a feather's ability to marry, but in actuality barbicels or perhaps more specifically hooklets is what was meant? If we spoke the same language we would better comprehend what was intended. It may not be necessary to know scientific names, but if we wish to communicate, we need to have standards.

Easy to learn

The parts of a typical feather are simple to learn, and once understood help us to better appreciate why feathers do what they do in different applications. For instance why does a dry fly hackle when wound on an uneven surface (i.e., twisted thread, bulky surface, etc.) lead to a fly with the barbs strewn all about? Why does a hackle mounted on an even surface produces a fly with barbs at a distinct ninety degree angle out from that surface? If you understand the rectangular shape of the rachis and the location of the barbs on the rachis it all makes sense. What does understanding of feather construction lead to? Better flies that we control rather than the material controlling us. It also leads to a more appropriate selection of materials for specific tasks.

To whet the appetite

This article is not intended to be a complete scientific discourse on the nature of feathers. Feathers are as unique as the birds that wear them. The following discussion is general in its scope while being specific enough to cover the majority of feather types that the fly tier will encounter. All the same great effort has been placed on accuracy of feather and component names and descriptions. Perhaps just as important has been a desire to whet the appetite of the fly tier toward a better understanding of not only physical construction, types, and purposes of feathers, but also to make that same tier more curious about other materials not understood. Observation leads to understanding. Understanding leads to better results in any endeavor. Sadly it is easier to take for granted what has been said in the past rather than investigate on our own.

Feathers at hand

It may prove beneficial to have a selection of feathers on hand while reviewing this article such as an eyed peacock upper tail covert, a turkey tail feather, a turkey "marabou" semi-plume, a ring-necked pheasant contour feather, and a rooster neck hackle.

Part of vane with pennaceous barbs.

Part of vane with plumulaceous barbs.

Base of shaft with whole quill.

The quill or calamus is often mistakenly described as being anything from the feather shaft to the barbs themselves. The fact of the matter is that the quill is simply that portion of the feather that is inserted in the skin follicle; nothing more. It is cylindrical, transparent, and hollow. There are no barbs attached to the quill.

The shaft or rachis is that portion of the feather that the barbs are attached to. It is flattened on the sides that support the barbs. It differs from the quill by being roughly rectangular in cross section. Internally it is not hollow, but rather is filled with a pithy material that contains air cells.

The barbs or rami (singular: ramus) come off the flattened sides of the shaft more toward the anterior (face) surface of the feather and in parallel rows generally opposing one another. They point outward and toward the tip of the feather. They are somewhat ovoid in cross-section (thinner side to side, wider front to back), broader near their attachment to the rachis, flattening and narrowing as they approach the tip. Barbs, like the shaft, are filled with a pithy material containing air cells. A feather may have only a couple of dozen barbs or several hundred.

Barbules

or radii (singular: radius) extend out from either side of the barbs. From the base to about half way to their tip, they are ribbon-like (the basal lamella). The distal half is more whip-like (the pennulum.) The barbules on the distal (upper) edge of a barb extend outward almost perpendicular to the barb. The barbules on the proximal (lower) edge of a barb lay more parallel with the barb. This is readily visible with a peacock upper tail covert feather's barbs, commonly referred to as "herl". (Herl according to dictionary definition is a barb or barbs of a feather, originating from the Middle English harle or herle which referred to fiber, hair of flax, or hemp.) Barbules extend out from a barb more proximal to the anterior (face) surface similar to barbs on a shaft. Again note the appearance of the peacock upper tail covert feather. When viewed from the anterior surface of the feather, the brightly colored eye is more dominate because the barbules (which often provide the majority of a feather's color) are attached closer to the anterior edge of the barb. When viewed from the opposing surface, the flat, rather dull color is due to the dominance of the color of the edges of the barbs as well as the location and physical shape, and in turn, light reflectance of the barbules.

Barbules may or may not have attached to them structures collectively referred to as barbicels. Barbicels allow adjacent barbules to interlock or marry. They differ on the barbule in shape and function by location.

Distal barbules (those extending off the barb toward the feather tip) with barbicels have projecting structures at the base of the whip-like pennulum (distal half of the barbule) on the ventral (under) surface that are long and hooked, hooklets (hamuli,) with the remainder of the pennulum having shorter spines (ventral processes).

Proximal barbules (those extending off the barb toward the quill) tend to be more twisted than the distal barbules, and have a trough-shaped dorsal flange (groove) on the anterior (front) edge. As the hooklets of a distal barbule overlap the adjacent proximal barbule, the hooklets attach to the grooved edge while the spines stop the hooklets from sliding too far.

The diagonal cross-over of barbules creates a visible herringbone pattern. Both distal and proximal barbules have other lesser processes on the underside of the ribbon-like lamella referred to as ventral teeth and on the upper side of the whip-like pennulum referred to as dorsal cilium and spines. The hooklets and spines create the marriage of the adjacent barbs while the dorsal processes and ventral teeth catch the barbs and barbules of overlaying feathers to help maintain a solid, air-tight surface in flight. In turn the feather vane is maintained as not only air tight, but with some birds, a water tight structure. Barbicels is a collective term referring to all the processes that interlock to create the vane.

The shaft gives support while the vane (vexillum) or the web of a feather (which includes all the flat, expanded barbs, as well as any attached barbules, and barbicels) provides the surface for an airfoil in flight feathers and for covering and insulation in contour feathers. At the typical feather's base, the vane is downy and provides some insulation. This part of the vane is referred to as the plumulaceous vane.

The remaining portion of the vane is more firm and compactly arranged, and is referred to as the pennaceous vane. Feather types are often defined by the proportion of plumulaceous and pennaceous material present. Some feathers are strictly plumulaceous, others are strictly pennaceous, and others are both plumulaceous and pennaceous.

Birds have a tremendous variety of combinations of feather components. For instance the Crowned Crane crest feathers are each made up of a short quill, a twisted rachis, and few barbs. What the fly tier considers the useable portion of a typical cocks hackle in a dry fly has few or no barbules on the barbs since those barbs with barbules are stripped prior to application.

Fly tiers somewhat incorrectly refer to this part of the feather as being the web or webby portion of the feather. Web is a term synonymous with the whole vane.

Some feathers have barbules without barbicels. Examples would include peacock upper tail covert feather barbs below the eye as well as down feathers from any bird. (When considering peacock herl, the barbs are often mistakenly referred to as quills. The barbules also are confusingly referred to as herl for example where the fly pattern for a Quill Gordon calls for a quill body that requires the removal of the herl from the barb. In actuality, the quill is a barb and the herl referred to are barbules on the herl or barb.) Barbicels are found on flight feathers (i.e., turkey tail feathers, peacock secondary wing feathers, etc.) with the exception of flightless birds (i.e., emu, ostrich, kiwi, etc.) Just as a barb does not necessarily have barbules, barbules do not necessarily have barbicels. Turkey marabou (semi-plume) is an example of a feather with barbules, but no barbicels. Body (contour) feathers of most pheasants are examples of feathers having barbules without barbicels (plumulacious vane) on some barbs and barbules with barbicels (pennaceous vane) on others.

Understanding marrying

The arrangement of barbs, barbules, and barbicels is important to understand when marrying feather strips for a wing on a wet fly or Atlantic Salmon fly. The marriage of a strip of upper barbs to a correctly matching strip of lower barbs is quite easy if the face side of the upper strip is placed slightly behind the face side of the lower strip. This allows the hooklets on the barbules of the top barb of the lower strip to have opportunity to grasp the grooved edge (dorsal flange) of the barbules on the upper strips' bottom barb.

If the strips are overlapped immediately above and below one another, or perhaps the upper strip is in front of the lower strip, due to their arrangement on the barbules, a complete interlocking of hooklets to flanges will not occur. If a strip is overlaid with another strip, but the matching strip is upside down, this arrangement of barbicels will not allow the strips to marry. If a right strip is overlaid with a left strip, even though the proximal to distal arrangement of the barbules is correct, no reliable marriage will occur, because the hooklets and flanges do not align.

Many feathers develop fault bars across the vane. As feathers grow, a disruption in cell development may occur leaving distinct lines across the vane generally perpendicular to the shaft. These are due to stress, other abnormal conditions, or may be present under normal conditions. A fault bar's appearance is due to underdevelopment of barbules or total lack of barbules in the area of the disruption.

Feather Types

Each feather grows out of the dermal tissue from a follicle in similar fashion to hair in mammals. Some feathers can be moved by muscles attached to the follicles. For example, tail and wing feathers can be adjusted to aid in flight. Body feathers can be erected independently or in groups for the purpose of body temperature adjustment as well as for display. Most feather follicles are well supplied with nerves, so it appears that feathers may serve as organs of touch. During development the feather is a living structure well supplied with blood, but once matured the feather itself is a dead structure. After a period of use it is shed or molted, and then replaced by a new feather from the same follicle.

There are two basic types of feathers from which others are derived; down feathers and vaned feathers. Down feathers are essentially random fluff having no barbicels on the barbules to interlock their barbs. In nestling birds down feathers consist of a tuft of barbs without a rachis. The juvenile and adult bird have down feathers that include a rachis. Vaned feathers include all feathers with a flat expanse of barbs extending parallel out from the shaft. Contour and flight feathers are pennaceous vaned feathers and are accepted as vaned feathers, where that plumulaceous feathers generally are not. Technically speaking, as discussed under Feather Anatomy 101, a marabou feather, though strictly a plumulaceous feather, is also a vaned feather. Down feathers, though plumulaceous, have a random arrangement of barbs, and thus would not be considered vaned.

Other feather types similar in some respects to down and vaned feathers while unique in others include filoplumes, bristles, and semiplumes. A filoplume (thread feather) is a hair-like feather with barbs at the end of the shaft. They are distributed to all feather types, are always intimate to other feathers (from one to twelve adjacent a feather,) but grow out of their own follicles. Their purpose seems to have something to do with subtle detection of movement of the adjacent feather such that they may, for example, aid in adjustment of feathers when in flight. (Filoplumes are sometimes incorrectly referred to as pinfeathers. A pinfeather is any feather that is immature.) Virtually all bristles are found on bird's heads. They are stiff with a tapered shaft having barbs only on the proximal portion of the shaft (i.e., Crown Crane crest feathers.) Often they are mistaken for filoplumes which differ by having barbs at the distal end of the shaft. A semiplume is a down-like (plumulaceous) feather having a rachis, barbs, and barbules, but no barbicels (i.e., marabou.)

Feather Names

Numerous specialized names are applied to feathers appropriate to their location on the bird, from the face to the toes, but there are just a few basic types that should concern most fly tying needs.

Contour feathers

Contour feathers cover the bird's body. They are close fitting, yet separated from the skin to help isolate the body from outside humidity and temperature. With the assistance of follicle muscles, the contour feathers can be erected, then lowered to adjust the depth of the protective layer. Contour feathers are typically broad, thin, curving inward toward the skin, directed toward the tail in overlapping rows, and have a combined pennaceous/plumulaceous vane. They help to smooth and streamline the body for flight. In some species they may be greatly modified for purposes of display or some other ornamental purpose. Many contour feathers have afterfeathers attached at the base. These are small plumulaceous feathers which may or may not have a shaft (hyporachis.) Usually a contour feathers' afterfeather is no more than half the length of the attached contour feather, yet exceptions always seem to occur in nature. Two birds, the Emu and the Cassowary, have afterfeathers as long as their contour feathers, while some birds such as the pigeon and ostrich have no afterfeathers.

Flight feathers

Flight feathers include the tail feathers (rectrices) and wing feathers (remiges) as well as supplemental feathers that cover the adjacent upper and under surfaces.

The tail feathers

The tail feathers (rectrices) act as a stabilizer tilting the front of the body up and down, as well as an air brake when the bird lands, but they are not used for steering except in steep turns. Tail feathers are usually large, stiff in texture, asymmetric, have vanes that are almost entirely pennaceous, and lack afterfeathers. In most cases tail assemblies are made up of 10-12 feathers (with some pheasants having up to 24) arranged in a single horizontal row. They each overlap their lateral (outside) edge over the medial (inside) edge of the adjacent feather. The outermost feather's lateral vane is narrow, stiff, and convex compared to the softer, longer, concave barbs of the inner vane. This effect is digressive as the feathers work toward the center pair, such that the center pair's vane is fairly symmetric right to left. The turkey tail assembly when fanned clearly demonstrates this. At the bases of the tail feathers are upper tail and under tail covert feathers that smooth and streamline the tail of the bird. Exceptions do occur such as with the peacock upper tail coverts, which lack streamlining, but are useful for display.

The wing feathers

The wing feathers (remiges) are used for steering. Like tail feathers, they are usually large, stiff in texture, asymmetric, have vanes that are almost entirely pennaceous, and lack afterfeathers. Wing feathers include primary, secondary, and tertiary feathers. The primary wing feathers (typically 10-11 in number) attach to the middle digit and the hand. They are asymmetrical in vane structure with the their leading and trailing margins notched. This sudden narrowing produces a series of slotted spaces between the primaries which in flight reduces air turbulence over the wing tips. Where turbulence is most extreme, the leading edge barbs are broadened and stiffened. These barbs are referred to in fly tying parlance as biots. The secondary wing feathers (anywhere from 9 to 40 in number and up to six inches wide by six feet in length) attach to the ulna of the forearm. The tertiary wing feathers attach to the humerus. There may also be a group of 3 or 4 feathers attached to the bones of the thumb forming a bastard wing (alula.) These feathers lie flat during normal flight, but extend out when flying slowly to prevent stalling.

Uniquely developed

Wing feathers may be uniquely developed for specific purposes. For example waterfowl wing feathers are designed to be water repellent. This is accomplished by modifications in the structure and position of the barbules such that a surface through which water cannot enter is created. They are so unique that a specific name is applied to this type of barbule/barbicel structure; flexules. The owl differs dramatically in having soft overlays of barbules on the surface of the feathers that keep it silent in flight.

The bases

The bases of the wing feathers as well as the upper and lower surface of the remainder of the wing are covered by several rows of small, flattened wing coverts (tectrices.) The largest wing coverts are adjacent the wing feathers digressing in size toward the wings leading edge. The vane is principally pennaceous and designed to supply an air-tight surface to the wing. The upper wing coverts, like contour feathers, are convex. Under wing coverts are concave, which fits them up into the underside curve of the wing. (This is an important consideration for the fly tier. For example in Frederic Tolfrey's Jones's Guide to Norway a component of "The Major's" wing calls for an overlay of "two snipe feathers." These are under wing coverts on the snipe, and thus are concave. Their natural shape forces the fly tier to carefully select a pair that will produce little or no outward curve when placed over the wing.) Those coverts on the leading edge of the wing initially extend vertically and then bend backward over the wing at an acute right angle creating a camber or upward curve.

Stages of plumage

A bird passes through various distinct stages of plumage. The plumage of the nestling stage is mostly down and contour feathers which plays a role primarily of warmth and concealment.

There may also be an intermediate nestling stage with yet a different plumage. The adult may have different stages of plumage such as immature, full adult, pre-nuptial, and courtship.

Male to female can be quite different, especially in the adult. Some immature birds take on the appearance of a mature female (i.e., some cockatoos and parrots.)

For the fly tier this can be of importance since some feathers in a fly may be obtainable only from an adult male, an adult female, an immature male and/or female, either the adult female or an immature bird, or perhaps any of these.

For example in The Salmon Fly, George Kelson's dressings for "The Silver Spectre" and "Prince's Mixture" call for the use of Black Cockatoo's tail. Experience teaches that the feather of choice is only found on female or immature male Red-Tailed Black Cockatoo mottled orange, black and yellow center tails. A mature male has completely different black-red-black center tails. Then in Francis Francis' A Book on Angling another dressing may simply read "Black Cockatoo or any other black feather." Here the feather becomes more obvious and might be either a strip from the black portion of an adult male Red-Tailed Black Cockatoo's tail, or better yet the all black tail of an adult male Palm Cockatoo.

Summation

The more the fly tier knows about the materials he has access to, the better his ability to select and apply the proper material to achieve the desired end result. Do not always accept what is read or told without a bit of personal investigation. Take time to look at materials. Feel them. Observe them under magnification. Do some homework in books such as Darrel Martin's Fly Tying Methods, which includes excellent microphotographs of all manner of tying materials. Knowledge of materials, dexterity, and experience are always found in abundance with the best fly tiers.

A quote from Mr. Martin's book sums up so well a great deal of the motivation for this article: "The birth of a fly begins with a feather. The tyer will require time and experience to know the various feather types, their numerous names, and their craft possibilities. The fly at the end of your tippet should be the result of all your knowledge and skill; it is the touchstone that drifts over the mystery of water and trout. After all, a fly is more feather than steel. It is the different feathers and the different methods that make a different fly". (Fly Tying Methods, pg. 59.)

Definitions

| Afterfeather | attached at the base of contour feathers; small plumulaceous feathers which may or may not have a shaft. |

| Barbicel | a collective term referring to all the processes found on the barbule that interlock to create the vane. |

| Barbs | sing ramus, pl rami; fibers that extend off the flattened sides of the shaft in parallel rows generally opposing one another; somewhat ovoid in cross-section; filled with a pithy material containing air cells. |

| Barbules | sing radius, pl radii; extend out from either side of the barbs; each is ribbon-like from the base to about half way to the tip and whip-like over the distal half. |

| Basal Lamella | ribbon-like base of the barbule; ventral teeth are attached to the under surface. |

| Bastard Wing | sing alula; feathers that lie flat during normal flight, but extend out when flying slowly to prevent stalling. |

| Bristles | generally found on bird's heads; stiff with a tapered shaft having barbs only on the proximal portion of the shaft. |

| Contour Feathers | cover the bird's body; typically broad, thin, curving inward toward the skin, and directed toward the tail in overlapping rows; help to smooth and streamline the body for flight. |

| Dorsal Flanges | trough-shaped proximal barbules that are more twisted than the distal barbules; hooklets overlap and attach to the flanges. |

| Flight Feathers | include the tail feathers and wing feathers as well as supplemental feathers that cover the adjacent upper and under surfaces. |

| Filoplume | synonymous with thread feather; hair-like feather with barbs at the end of the shaft, always intimate to other feathers (from one to twelve adjacent a feather,) but grow out of their own follicles. |

| Hooklets | pl hamuli; hooked barbicel structures on the distal barbules that overlap and attach to opposing dorsal flanges. |

| Pennaceous | referring to barbs having barbules with barbicels that interlock adjacent barbs. |

| Pennulum | whip-like tip of the barbule; hooklets are attached to the proximal, ventral portion with the dorsal spines and dorsal cilium attached to the remainder of the pennulum. |

| Pinfeather | any feather that is immature. |

| Plumulaceous | referring to downy like barbs having barbules without barbicels. |

| Primary Wing Feathers | typically 10-11 in number; attach to the middle digit and the hand; asymmetrical in vane structure with the their leading and trailing margins notched. |

| Quill | sing calamus; that portion of the feather that is inserted in the skin follicle. It is cylindrical, transparent, and hollow having no barbs attached. |

| Secondary Wing Feathers | from 9 to 40 in number; attach to the ulna of the forearm. |

| Semiplume | a plumulaceous vaned feather (i.e., marabou.) |

| Shaft | sing rachis; that portion of the feather that the barbs are attached to; flattened on the sides that support the barbs; roughly rectangular in cross section; filled with a pithy material that contains air cells. |

| Spines | ventral processes on the distal barbules that stop the hooklets from sliding too far and collapsing the vane. |

| Tail Feathers | pl rectrices; large, stiff in texture, asymmetric, have vanes that are almost entirely pennaceous, and lack afterfeathers; act as a stabilizer tilting the front of the body up and down, as well as an air brake. |

| Tertiary Wing Feathers | attach to the humerus. |

| Upper and Under Tail Covert Feathers | smooth and streamline the tail of the bird. |

| Vane | sing vexillum; the web of a feather which includes all the flat, expanded barbs, as well as any attached barbules, and barbicels which provide the surface for an airfoil in flight feathers and for covering and insulation in contour feathers. |

| Vaned Feathers | a collective term generally referring to a feather that has at least some interlocked barbs as seen in contour, wing, and tail feathers on birds that can fly. |

| Web | synonymous with vane. |

| Wing Coverts | pl tectrices; cover the upper and lower wing surfaces and the bases of the wing feathers. |

| Wing Feathers | pl remiges; usually large, stiff in texture, asymmetric, have vanes that are almost entirely pennaceous, and lack afterfeathers; used for steering. |

References

| Alfred M. Lucas, Ph.D., Peter R. Stenttenheim, Ph.D., Sept. 1972 | Avian Anatomy - Integument, Part I |

| Gary A. Borger, 1991 | Designing Trout Flies |

| Edited by Dr. Christopher M.Perrins and Dr. Alex L. A. Middleton, 1985 | The Encyclopedia of Birds |

| Darrel Martin, 1987 | Fly Tying Methods |

| Joseph M. Forshaw, 1977 | Parrots of the World |

| R. Garth Coghill, 1989 | "Traditional Quill Wings From Flight Feathers" |

With thanks to my friends Marvin Nolte (U.S.A.), Martin Jørgensen (Denmark), Garth Coghill (New Zealand) and Thomas Whiting, Ph.D.(U.S.A.) for their advise and comments.

April 1996

- Log in to post comments

Wayne,

This is the

Wayne,

This is the most comprehensive feather anatomy article that I have ever read, I never had such an inclusive course in college biology classes. Tyers should not be intimidated by the singular and plural names of the feather parts; as a tyer they know which part they need to use to construct their chosen flies. It is very beneficial to know about the hook sites on the specific feathers used to marry salmon fly wings. Martin pointed me to your Feather Anatomy 101; thank you Martin.

Currently, I am reading a fascinating book by Thor Hanson of our US Pacific Northwest; it is Feathers, The Evolution of a Natural Miracle. It is definitely scientific because it is in the Natural History category. However, Thor has broken up the heavier sections with very interesting personal stories. I highly recommend Feathers.

Mohan,

I'm not su

Mohan,

I'm not sure I get the question...

Birds use feathers for flight and insulation.

We fly-tyers use them for tying fishing flies

Other uses could be pillow stuffing, ornaments, clothing and much more

Martin

what are the uses of

what are the uses of feather and where it is used and mention its purpose of feather

Great diagrams. Ans

Great diagrams. Answers my questions. Clearly stated.

What about the downy

What about the downy feathers?

it has a quill,barbs

it has a quill,barbs and barbules, what is it ?

Mossfire: Me too! Ca

Mossfire: Me too! Can you write me, please? We could make an interesting exchange.

this would have been

this would have been great with photos attached of a steadily dissecting wing/cape/whole skin as each feather comes away.

Hi hello there i'm a

Hi hello there i'm a native from U.S.A. i just have a question what if i native wants tail feathers from these cockatoo for ceremonial purpose can it be send to or not .......?

After all these year

After all these years of looking at the similar diagrams, this one has provided a comprehensive understanding in a flash.

Hi there... I am ver

Hi there... I am very interested in feather.. did any body know where I can get the info regarding horw the feather grow.. their contents and etc... pls help..

I am studing the ana

I am studing the anatomy of a birds wing and to rember it, I needed to know the atamoy of the feather. This sight was very useful! I was calling the shaft the steam, and I had no ides what to call the barbs (I would have been really embarrest if I showed my little report to some one who know what was what). I collect feathers and I always try to look up what kind of bird it was from, but the books ues these sientific words and I had no idea what they were. Now I do! Thank you so much!

does anyone know wha

does anyone know what the longest quill feather is called?

Thank you for this u

Thank you for this useful information.