Knots have challenged author ron P. swegman all his life. When he was a preschool boy, he demanded his mom buy him “buckle shoes” because he just could not get the hang of shoestrings.He reflects further over knots in this latest chapter of the online novel "Small Fry".

There are improved knots and knots not to do.

Sometimes the unexpected breeds anger

As when a bad cast brings on the miscue.

The trout can be tricky and selective.

The bass can break a line with sheer brute force.

These moments can make fishers reflective.

This is the nature of the sport, of course.

What tie is best for the situation?

What is the best way to prevent tangles?

How can a fisher avoid frustration?

How not to curse while the angler angles?

The answer begins with patience, a lot,

Followed by the fine end -- the well-tied knot.

What is the smallest part of all fly-fishing? I would have to place my discretionary coin on knots. These integral, intertwined lengths of horse hair, silk, linen, monofilament, or fluorocarbon fishing line are usually no more than one square millimeter in size, yet they are the largest and most vital link in the chain that tethers fisher, fly, and fooled fish.

“Knot me!”

Knots have challenged me all my life. When I was a preschool boy, I demanded my mom buy me “buckle shoes” because I just could not get the hang of shoestrings. Reflecting on this now, I am convinced the problem stemmed from my being left-handed. My right brain could not follow the “in and out and over and through” directions for the longest time; I was pleased to learn much later that no less a genius than Albert Einstein had suffered from the same problem.

I eventually learned to tie my shoes by following each step in a mirror. We had a tall, narrow one leaning against a wall in our home so a person could get the kind of floor to ceiling full fashion view common in clothes shops. I followed that opposite image, which helped my southpaw point of view follow through so I could wear a pair of hip, brown suede Hush Puppies to kindergarten.

A year later, when I began to fish, knots returned as an issue of contention. Wisps of 6 lb. test line, blown and twisted by the wind, were difficult for my young fingers to control, and unlike my shoestrings, I could not untie and try again. Fishing knots, I found, were permanent. So, each time I made a mistake, I would have to cut the line and start over. The fish, I noted, were always biting especially well at such times.

I was a big fan of Dr. Seuss and his books back then, and I remember one of his characters who always stated “Not me!” when asked if he (or she or it?) had done something or other. My maternal grandfather, Robert L. Bogaski, a painter and professional illustrator himself, had a skillful hand and patient manner ideally suited for his role as my first fishing guide. I was neither bold enough nor lazy enough to utter such a defiant line to him, so I never pulled a tantrum or refused to rig up myself under normal conditions. Sometimes, though, the wind or sheer excitement got to me, and in one such instance, during a gray April gale, my first original pun was born when I turned to him, the tip of my twisted leader in hand, and asked: “Knot me!” He laughed and then helped me assemble my simple hook and sinker rig. A sense of humor, I learned, came in handy at the fishing hole.

That summer I learned to tie the two most common, and some would say “best”, basic fishing knots -- the clinch knot and the improved clinch knot -- by practicing with the jute twine my mother used for green pea and pole bean trellises in her vegetable garden. The thick strands were easy to work with, and I soon got the hang of twisting the line several times around itself, followed by threading the loose end through the loop at the base. No bluegill or yellow perch would be safe from my worm.

What wisdom I had yet to absorb was patience along the water. This lesson, perhaps as important as mechanics to knot tying, is tough; I am still learning.

One of my family’s favorite fishing destinations has been Lake Arthur: a 3,225-acre impoundment situated fifty miles north of my home city of Pittsburgh. An aerial view of the lake resembles a striding cougar -- head to the northwest, four legs to the south, with a tail leading northeastward -- a feline image as believable as the constellation of Leo the Lion. This lake, then as now, is regionally famous as a trophy channel catfish and black bass lake and is Pennsylvania’s best bet for a largemouth bass exceeding eight pounds. Smallmouth bass are found here as well.

A nice geographical feature of this lake for anglers is the presence of numerous secluded coves the size of farm ponds. These spots are frequently surrounded by trees that line their circumference and lead to narrow inlets, which make ideal gathering places for schooling crappies and spawning sunfish in spring and cruising bass all year long.

My mother and stepfather were wet wading and fly casting their poppers and deer hair bugs among the lily pads of one of these coves as I fished a night crawler beneath a bobber from dry land; my introduction to fly-fishing was still several year off, and I was content, as float fishing allowed me time to indulge my junior scientist’s interest in birds and the numerous little invertebrates that called the weedy, reedy, undeveloped shoreline home.

The sunfish started biting with abandon near dusk. Excitement filled me. Judgment left me. I missed one hit, which somehow snagged the hook onto a patch of pads. The tenacious stem would not let go, the line snapped, and I reeled in the loose end as quickly as I could. I hurriedly slipped another snelled size 6 Eagle Claw from its pack and, to save precious daylight time, quite foolishly tied it onto my line with the first knot I had mastered -- the shoestring bowtie.

My next hit was a whopper that pulled under my bobber so hard that it made a splash. I pulled back and felt a resistance as forceful and as heavy as the stem had been, but this connection moved with a mind of its own. A largemouth bass as broad as a football broke water ten feet in front of me, flipped its rear end in my direction, and broke off at the knot. I dropped my rod and started to cry. Soon my wails were so loud that my parents practically ran into shore, fearing I had injured myself. I was hurt all right. I had been burned, but I had learned . . . sort of!

Knot Sense

There is another kind of knot, the kind angler’s study to avoid. Call it a tangle, or more accurately, a bird’s nest. These are knots not of seamless strength and beauty, but rather of pure chaos that can make a priest curse.

How do such messes of line form? The answer can be tied -- pun intended -- once again to patience, or more precisely, a lack thereof. Almost every bird’s nest occurs because an angler tries to fish faster than the gear, weather, or water conditions will allow.

A backlash on a bait casting reel usually occurs when the caster is all thumbs in the wrong way. I learned this fishing off the piers along Virginia Beach. When the schools of flounder and spot began their summer evening feeding frenzy, the entire pier buzzed with the electricity of “Fish on!” excitement. Sometimes, at such times, my urge to cast was so strong that some important steps, such as using the casting thumb to control the forward flow of the line, were forgotten. The result was a bird’s nest in my hand and a bushel basket of fish for the person angling next to me.

Spinning snarls develop for the same reason. Excitement, bragging, or story telling while casting can cause the guilty party to close the bail too quickly, before the bait or lure hits the water. This creates backward momentum, a bird’s nest, and all-to-often, new, inventive bad language. Silver lining: If a fish happens to strike while pulling in the length of clipped off monofilament, an angler can receive a crash course in hand-lining.

Life experience is telling. I was once a boy, spin-fishing along Laurel Hill Creek, during an opening day weekend in early April. Big rock bass were not on the agenda this time out. Trout were, and I was prepared, yet a knot came in between me and the fish in the most ironic of ways.

Friday evening before the opener witnessed the traditional exodus from the shop floors and office towers that coalesced into the extended annual gathering of the angling tribe at the family cabin. The first night was a party of preparations, food, and fish stories. Being the young one, I was sent off to bed first, although I had to feign sleep on the cabin’s sagging living room couch. The adults nearby were playing cards around a very rickety, and noisy, kitchen table. A bottle and several glasses added more musical percussion. At one point a whisky voice remarked: “Ah, look at him, sleeping there. I bet he’s having dreams of 10-pound rainbows!”

Opening day passed, and dreaming was as close as I had come to netting a fish. I had been skunked. I became the joke of the party. Sunday arrived, and after another empty morning, the reality descended upon me like rain clouds: we were going to be leaving in a few hours. The rest of the group was content to load up their cars and pickup trucks with the gear and a limit of frozen, stocked, foot-long trout. My immediate family took pity, relieved me of packing chores, and let me fish a little while longer.

I was casting and retrieving a silver Mepps spinner along the rocky ledges of the pool above the cabin, still with no success. The clock was racing and so was my mind. I had to catch one. Just one! I rushed myself, and a bum cast left me with a major snarl. No time to sit on the bank and fiddle-faddle. I clipped the line and started to pull it in hand over hand. Suddenly, the big one hit! Fish and spinner raced upstream, against the current. My charged state somehow kept up with the fish. A crowd gathered. Dropped jaws cheered me on as I finagled an 18-inch rainbow trout to shore. Not quite a 10-pounder, but I won the betting pool with that fish and had no doubt showed up the whisky-soaked wiseguy who had mocked me two nights earlier.

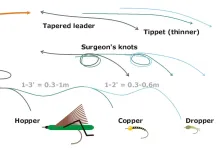

Fly casters encounter knots of the unwanted kind most often along the leader or tippet. I have found that tandem rigs are particularly susceptible. Erratic currents, fast water, and once again, a lack of patience, are the primary causes. If the cast is not allowed to follow through, indicator and dropper will tangle effortlessly together.

Another trip to my beloved Wissahickon Creek taught me this knot lesson. One exceptionally calm and deep green June evening, a hatch started, stirring two or more brown trout at the tail end of one of my favorite pools. I had long desired to score a double header -- an inside-the-creek, two-trout, home water run -- and this seemed to be the time and the place, and these appeared to be the trout. So, I clipped off a foot of fluorocarbon, tied on a small American Pheasant Tail nymph, and attached it all to the bend of my larger Olive Stimulator. Jitters of excitement filled my stomach, not with nervous butterflies, but with metaphorical mayflies.

I made one good cast without a take. Another two trout sips sent ripples down the otherwise unlined face of the run. Eagerness creased my own, replaced good knot sense, and my form on the follow-up suffered. I yanked rather than rolled, which made me groan as I watched nymph and dry fly begin to dance cheek-to-cheek. I found myself witnessing the airborne creation of a new “tumbleweed knot” I could have never devised by my own design.

The hatch ebbed and the sun set. I cycled home with more than another fishless story. The Wissahickon had imparted wisdom. A sudden hatch can cease just as quickly as it starts. This is no time to be untangling unwanted knots. Patience is more than a virtue at such moments; it is good fly-fishing.

- Log in to post comments