The father of English fishing literature, Izaak Walton, devotes two chapters of The Compleat Angler to chubs (or “cheven” in the archaic plural), and in one scene his Piscator takes pleasure in catching the largest one of a school of twenty to the amazement of his companions, Venator and Auceps.

The father of English fishing literature, Izaak Walton, devotes two chapters of The Compleat Angler to chubs (or “cheven” in the archaic plural), and in one scene his Piscator takes pleasure in catching the largest one of a school of twenty to the amazement of his companions, Venator and Auceps.

The chub’s status as a literary fish did not start and end with Walton. John Gierach wrote a humorous essay on “The Less-loved Fishes” like the squawfish, the super minnow of the Rocky Mountain's western slope (which Thomas McGuane also mentions in his essay "Angling Versus Acts of God"), and the chub does fit distinctly into this category. The trend has continued into the Twenty-First century with scenes from How to Fish by the British author Chris Yates as well as Richard Chiappone’s overt love letter to this little fish -- “The Chubs” -- which appeared in the angling anthology City Fishing.

So, what is the allure of this mighty minnow?

The Golden Guide classic, Fishing, states that “chubs are large minnows and some of them are sporty panfish.” The key term here is “sporty.” From Walton to Whitlock, anglers generally agree that engaging a hooked fish is the sport and soul of fly-fishing. The “sporty” chub family must be recognized, then, for these fish often rescue one’s morale along a stream where recalcitrant trout are failing to fully participate in the fly-fishing experience.

Creek chubs, river chubs, and fallfish are Cyprinids, and can be found in the coldest, clearest, sand and gravel streams from Canada , south to the mountains of Georgia , and west to the Ozarks. These fish demand the same pristine, oxygenated, flowing water as their stream fellow the brook trout and should be respected for that fact alone. The chub family also brings another endearing quality to those who love the tying bench, and that is their readiness to rise to dry-fly patterns.

If nothing else, think of the chub as a dry-fly sparing partner in preparation for an evening bout with the heavyweight trout. Picture this scenario: You arrive along a nice stretch of trout water, but there is no hatch in progress, the angle of the sun is wrong, it’s hotter than you expected, and the Salvelinus fontinalis are uncharacteristically skittish. No need to pack up and drive somewhere else. Tie on a small (size 14 or 16) Quill Gordon, or a Dark Hendrickson, or a Deer Hair Caddis. Practice your upstream presentation, and -- “Whoa!” -- an unexpected rise, a fish on line, and a respectable battle as a half-pound creek chub comes to the net.

Chubs and fallfish often school around loose pods of trout in a stream, especially during high summer’s low water conditions. Sight fishing for chubs then can be easy, and there is no reason to believe the chubs are hogging the action. The trout are almost always off the bite at such times and are waiting instead for the evening light and the evening hatch. “Practice” with chubs can prepare you for “perfect” with trout and will at the very least let you return home without a goose egg.

The Clarion Call of “Junior Trout”

My mother’s parents would give her a well-earned vacation every first week of July by taking me along with them to visit Uncle Herb Miller, who served as year-round caretaker of the family's Pennsylvania property outside of Marienville in Forest County. We called our bucolic spread “The Mountains” and that was an appropriate moniker. Forest County was once the hunting grounds of the Seneca Nation of the Iroquois Confederacy and these steep river valleys continue to sustain impressive old growth stands of eastern white pine and eastern hemlock both in Cook Forest and the southern portion of the Allegheny National Forest.

Fishing by day and penny poker by night awaited us all at Uncle Herb’s. Card games were played along the long table in the cabin’s combined dining and living room area, and game fish were played along the boulder gardens of the Clarion River.

The Clarion, the main tributary of the Allegheny, is one of Pennsylvania ’s designated scenic rivers and a world-class destination for canoeists. The river holds the reputation for the Commonwealth’s densest population of lunker brown trout, a good population of smallmouth bass, and plenty of chubs and fallfish. “Turtle Rock” was our family’s de facto spot along the river. The big stone did indeed resemble the shell of a giant prehistoric turtle and was wide enough to accommodate a base camp of up to six anglers, which was sometimes necessary when various aunts or uncles decided they wanted to test their luck at the family pool. A good aura of fortune lingered there after the fabled evening when my Grandma Bogaski somehow fooled, hooked, and landed a fourteen-inch trout in the heat of full summer.

One warm weather activity I had not yet mastered at that time was the essential skill of swimming. Being a latecomer to the sport, this posed a small, yet serious, piscatorial concern for my folks. A family powwow was held around the poker table. Uncle Herb had thin, angular facial features -- he resembled the classic image of the fisherman, complete with hat and wicker creel, depicted on magazine covers during the 1940's and 1950's -- yet these softened at the sight of me, bespectacled and pale, pouting and shaking from the fear -- the horror! -- that I might not be allowed to fish during my first mountain vacation. Grandpap Bogaski, who looked to me like a reincarnation of Benjamin Franklin, saved my day when, true to that statesman's tradition, he came up with a compromise.

It was decided that I could fish, but under the one condition that would allow the rest of the family to spread out and work the water. I thus found myself sitting, legs outstretched on Turtle Rock, leashed at the waist with a length of rope, the other end of which was attached to a nearby tree. The family was free to roam and I was free to fish -- still fish -- in safety.

Locked in place like a reel to a rod, I learned early on to contemplate and read the water. It was at these times when I perceived some of the summertime habits of the chub and fallfish. Small schools of cruising fish would sweep into the family pool at regular intervals and swim more or less in unison along the curving bend of Turtle Rock where its edge dropped off into the deeper water. Trout were occasionally in the mix. I never managed to lure any of these “brownies” to my baited hook, but I did catch more chubs that I could count, and the great action more than made up for the slight humiliation I felt at being tethered to a tree trunk. I came to call the chubs “junior trout” because of their size, sport, and general resemblance to the larger, spotted fish my Uncle Herb was so adept at bringing to his net.

The High School Degree

I mastered the basics of fly rod technique and learned to tie my first fly pattern a few years after that checkered initiation to the fishing vacation. My "Swegman's Special" was a simple grey nymph that lured the sunfish from my local lakes and, later in the fishing season, the creek chub, when our family traveled farther north to cooler, more mountainous settings. My contemporary take on this practical tie utilizes a material ideally suited for a nymph's subaqueous performance: knitting wool. To complete the recipe, simply tie in two pheasant tail fibers for the distinctive nymph's tail, followed by two fine strands of gray baby ull knitting yarn wrapped forward and around a standard wet nymph fly hook (for example, a Mustad 3906). Fished upstream, with or without an indicator, this pattern will be chased by a creek's chubs all afternoon and into the evening.

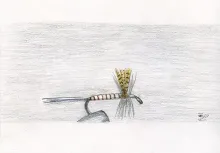

The dry fly remains the most rewarding, and sporting, way to take a creek chub or fallfish on a fly rod. Here is where universal respect must be paid to the Cyprinid. The creek chub has never fallen into angling fashion, like the introduced and naturalized common carp, simply because it can be taken on a fly rod. The chub is, rather, the undeniable real thing; a native and dry fly stream fish. Too illustrate further, I'll offer up another scene from my early days, another quick portrait of the angler as a young man...

My stepfather took me to the northeastern corner of the Allegheny National Forest near the New York border for a long weekend in late August just before I started high school. We camped at the mouth of Willow Creek where it enters the Willow Bay of the 12,000-acre Kinzua Reservoir. We canoed and fished, together and apart, for three end-of-summer days. During that time, with a great deal of stealth and patience, my stepfather managed to catch one magnificent fifteen-inch brook trout. I still have a faded color instamatic photo of that fish, and whenever I contemplate it, I also remember how sporty creek chubs saved my own fly-fishing expedition.

While my stepfather methodically worked his own dry fly patterns around the mouth of the bay for a trophy trout, I hiked upstream in my cargo shorts and Converse sneakers and spent several long afternoons exploring and wet wading Willow Creek. The image of me at play as I worked my way upstream might have resembled the sartorially updated likeness of another Pittsburgh native turned fly fisher -- Theodore Gordon. He, the father of the American dry fly, often fished a Catskill river called the Willowemoc. Such coincidental parallels of place and name can lead one to wonder in hindsight but, during those days when I wandered up Willow Creek, my focus was on the stream ahead. The flow was very low, its bed consisted more of dry stones than wet water, but shallow pools held tight to the grassy banks along each of its numerous bends. Here I could float my approximation of my predecessor's namesake Quill Gordon for a reasonable stretch, and I was rewarded with one or two surface rises per pool. The fish that were striking had a familiar look: silver sides, burnished backs, and a few scattered black spots. Some even jumped when hooked. The fish were creek chubs, and I managed to catch each and every one on a dry fly.

To this day I like to think I earned my high school degree in fly-fishing during that trip, and I have the humble chub to thank for it.

The Chub Kit

Basic Rig

3- to 5-weight fly rod and reel outfitted with floating line.

Fly Box

1) Adams, size 10 -- 16

2) Deer Hair Caddis, size 10 -- 16

3) Gray Wool Nymph (Swegman's Special), size 10 -- 16

4) Quill Gordon, size 10 -- 16

5) Zug Bug, size 10 -- 16

Other Necessities

Hemostats, insect repellent, non-toxic split shot, polarized sunglasses, small landing net

- Log in to post comments